Main Problem: Malnutrition in the ICU

When patients are not stable enough to be confined in a hospital room or ward, they are admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU). During this critical stage, the patient is likely to be in a hypermetabolic state, has higher calorie and protein deficit, has faster protein catabolism, or a combination of these. These factors contribute to malnutrition, which in turn may cause poor clinical outcomes, among which are nosocomial infections, prolonged ICU and hospital stay, and increased mortality.1

Nutrition management is therefore crucial to address these surrounding factors and prevent worsening of outcomes.

Currently, there is still no published set of ICU nutrition guidelines from the Philippine Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition (PHILSPEN). Therefore, most of this article draws from the 2018 guidelines of the European Society for Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism (ESPEN) and the guidelines of the American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition (ASPEN).

Critical care nutrition therapy is a way of supplementing nutrition to a critically ill patient to address malnutrition and prevent loss of lean body mass. It should be considered for all ICU patients unless contraindicated. Before initiating critical care nutrition, the Nutritional Support Team (NST), usually consisting of clinical nutrition physicians, RNDs, nurses, and pharmacists should first assess the level of malnutrition.

Nutritional Risk Assessment: The NUTRIC Score

The consensus statement states that on nutrition therapy for critically ill patients across the Asia-Pacific and Middle East regions, all patients admitted at the ICU should have nutritional risk assessment within 24 hours of admission, or as soon as possible.2 Nutrition risk assessment should be performed using a validated tool, such as the Nutrition Risk Screening 2002 or the Modified Nutrition Risk in Critically Ill (NUTRIC) score.

The NUTRIC score is the most commonly used tool for ICU patients and quantifies a patient’s condition, specifically the risk for developing worst-case scenarios. The NUTRIC score variables are shown below:

Table 1. NUTRIC Score Variables and Score (Critical Care Nutrition, n.d.)

| Variable | Range | Age |

|---|---|---|

| Age | < 50 50 - <75 ≥ 75 | 0 1 2 |

| APACHE II (Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation) | < 15 15 - <20 20 - 28 ≥ 28 | 0 1 2 3 |

| SOFA (Sequential Organ Failure Assessment | <6 6 - <10 ≥ 10 | 0 1 2 |

| Number of Comorbidities | 0-1 ≥ 2 | 0 1 |

| Days from Hospital to ICU admission | 0 - <1 ≥ 1 | 0 1 |

| IL-6 | 0 - <400 ≥ 400 | 0 1 |

The categorizations based on the availability of interleukin-6 values are shown below. The presence of IL-6 is usually associated with inflammation.

Table 2.1. NUTRIC Score scoring system: if IL-6 is available (Critical Care Nutrition, n.d

| Sum of Points | Category | Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| 6 - 10 | High |

|

| 0 - 5 | Low |

|

Table 2.2. NUTRIC Score scoring system: if no IL-6 available

| Sum of Points | Category | Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| 5 - 9 | High |

|

| 0 - 4 | Low |

|

Note. It is acceptable to not include IL-6 data when it is not routinely available; it was shown to contribute very little to the overall prediction of the NUTRIC score.3

The NUTRIC score is highly predictive and quantifies risk quite well. This is because it gathers specific data points instead of subjective measurements.

A less commonly used method for assessing risk in critically ill patients is using the ESPEN guidelines.4,5 According to ESPEN consensus, a patient is at risk for malnutrition if:

- Patient’s BMI is lower than 18.5 (<18.5 kg/m2) or

- Patient presents with unintentional weight loss of >10%, indefinite of time; or weight loss of >5% over the last 3 months, combined with either:

- BMI <20 kg/m2 if patient is <70 yrs. old, or BMI of <22 kg/m2 if ≥70 yrs. old, or

- Fat-Free Mass Index (FFMI) of <15 kg/m2 in women and 17 kg/m2 in men

The Factors to Consider in Critical Care Nutrition Therapy

In administering nutrition therapy for the critically ill, there are two main routes: enteral (EN) and parenteral nutrition (PN).

- Enteral Nutrition (EN) - more commonly known as ‘tube feeding’, means directing nutrition straight to the stomach or the small intestine

- Parenteral Nutrition (PN) - also known as ‘intravenous feeding,’ aims to deliver nutrients, such as proteins, carbohydrates, electrolytes, and lipids, straight to the bloodstream via venous entry through a peripheral line or a port

EN is usually administered to patients who are clinically unable to feed orally but have intact gastrointestinal (GI) function, such as in cases of stroke, anorexia secondary to cancer and/or treatment, and failure to thrive in infants, among others.

Significance of Feeding the Gut

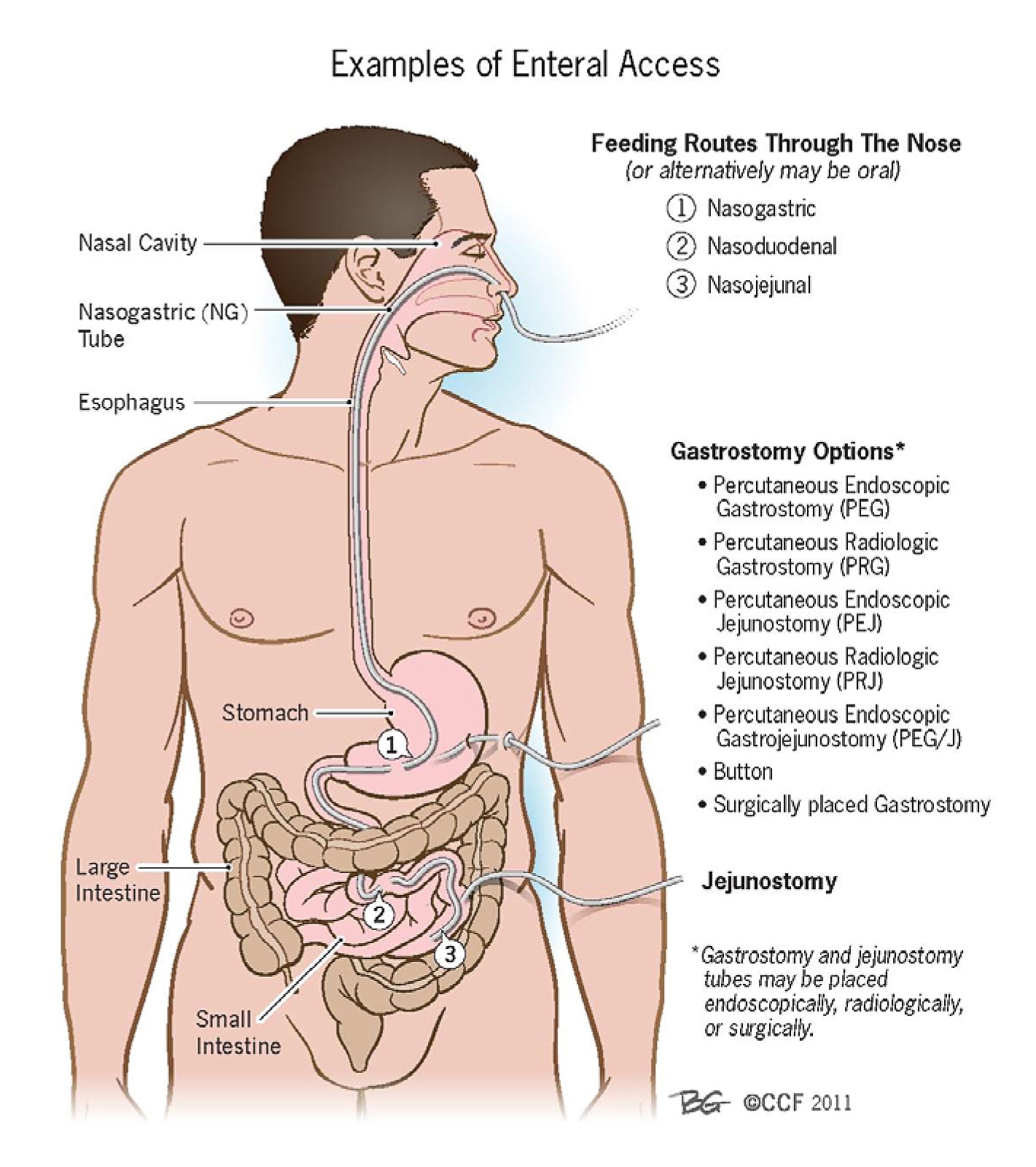

Figure 1.What is Meant by and What are Examples of Enteral Access? Enteral Access (American College of Gastroenterology, 2021)

The most important stimulus for maintaining intestinal function is the presence of luminal (enteral) nutrition. Food or enteral nutrition supports mucosal immunity and integrity of the GI tract by modulating mucosal cell turnover, stimulating blood flow to the gut to improve motility, reducing the risk of bacterial translocation and sepsis.6

Table 3. Routes and Benefits of Enteral Devices

| Enteral Devices | Route | Advantages |

|---|---|---|

| Nasogastric tube | Tube is inserted through the nose and led to the stomach | Easily maneuverable into placement and has various sizes |

| Orogastric tube | Tube is inserted through the mouth and led to the stomach | Does not often cause sinusitis or nasal discomfort compared with NGTs |

| Nasoentric tube | Tube is inserted in the nose and led to the small intestine | Less patient discomfort because thinner than NGTs and may be used in delayed gastric emptying |

| Oroenteric tube | Tube starts in the mouth and ends in the intenstines | Same as orogastric tubes |

| Gastrostomy tube | Tube is placed through the skin of the abdomen and led straight to the stomach | Convenient in terms of care and replacement, and has a large bore useful for bolus feeding and for administering medication |

| Jejunostomy tube | Tube is placed through the skin of the abdomen and led straight into the jejenum | Lower chance of food and fluids going into the lungs, and enables early postoperative feeding |

Table 4. Types of Parenteral Nutrition

| Enteral Devices | Route | Advantages |

|---|---|---|

| Peripheral Parental Nutrition | Utilizes peripheral vein as peripheral lines (Peripheral line types: short and midline)** | Only partially supplies daily nutritional needs to support enteral or oral feeding |

| Total Parental Nutrition | Utilizes a central venous cathedral* or a peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC) | Can supply daily nutritional needs* |

*Sourced from Total Parenteral Nutrition - Nutritional Disorders11

**Sourced from The Hitchhiker’s Guide to Parenteral Nutrition Management for Adult Patients12

On the other hand, PN is the route of choice if nutrients need to be delivered straight to the bloodstream because the oral or enteral route is inaccessible or contraindicated. Nutritional admixtures are delivered via ‘ports’ in the skin. Examples of cases needing PN are ischemic bowel disease, some types of cancer, bowel obstruction, protracted ileus, and other conditions wherein there is insufficient gut circulation.8

For patients with high nutritional risk, supplemental PN can be considered if EN fails to provide more than 60% of the nutrition goal after 3 days for both calories and protein.7,9

Table 5. Comparison of the Different Types of Critical Care Nutrition Support

| ENTERAL NUTRITION | PERIPHERAL PARENTERAL NUTRITION | TOTAL PARENTERAL NUTRITION | |

|---|---|---|---|

| DEFINITION | Directions nutritional feed through the nose or mouth to components of the GI tract, usually the stomach or intestine | Parenteral nutrition wherein the patient gets only some of the nutrients from parenteral formula. In this case, the main source of nutrition is obtained either orally or via EN, and PPN is only a supportive source. | Parenteral nutrition wherein the patient gets all the nutrients from parenteral formula. |

| INDICATIONS | When patient does not have the ability to chew or ingest food via mouth but has a function GI tract | For short-term use only and as a secondary source of nutrients if the patient cannot ingest food or cannot tolerate EN | When a patient's GI system has low absorption secondary to decreased perfusion to the gut, or when there are other conditions in which the gut is unable to absorb nutrients. |

| CONTRAINDICATIONS | High rish for nonocclusive bowel necrosis, generalized peritonitis, intestinal obstruction, surgical discontinuity of bowel, paralytic ileus, intractable vomiting/diarrhea refractory to medical management, known or suspected mesenteric, ischemia, major GI bleeding high output uncontrolled fistula | Patients requiring long-term therapy; markedly hypermetabolic and fluid restricted; inadequate peripheral venous access; presences of highly prone to phlebitis | Where gastrointestinal feeding is possible; patients with good nutritional status in whom only short term TPN support is anticipated; irreversibly decerebrate patients, lack of specific therapeutic goals; severe cardiovascular instability or metabolic derangements; infants with less than 8cm of small bowel as it has been conclusively proven that they cannot adopt to enteral feeding despite prolonged periods of |

| In most cases, EN is preferred over PN, and only when the GI is not functioning properly or when EN is not delivering enough nutrients will PN be administered. |

Additionally, Total Parenteral Nutrition (TPN) means supplying the patient with nutrition solely through PN, as opposed to peripheral PN (PPN), wherein the patient can still consume sustenance orally or via EN. In the latter, PN is only supplementary to the nutrition obtained orally or enterally.10

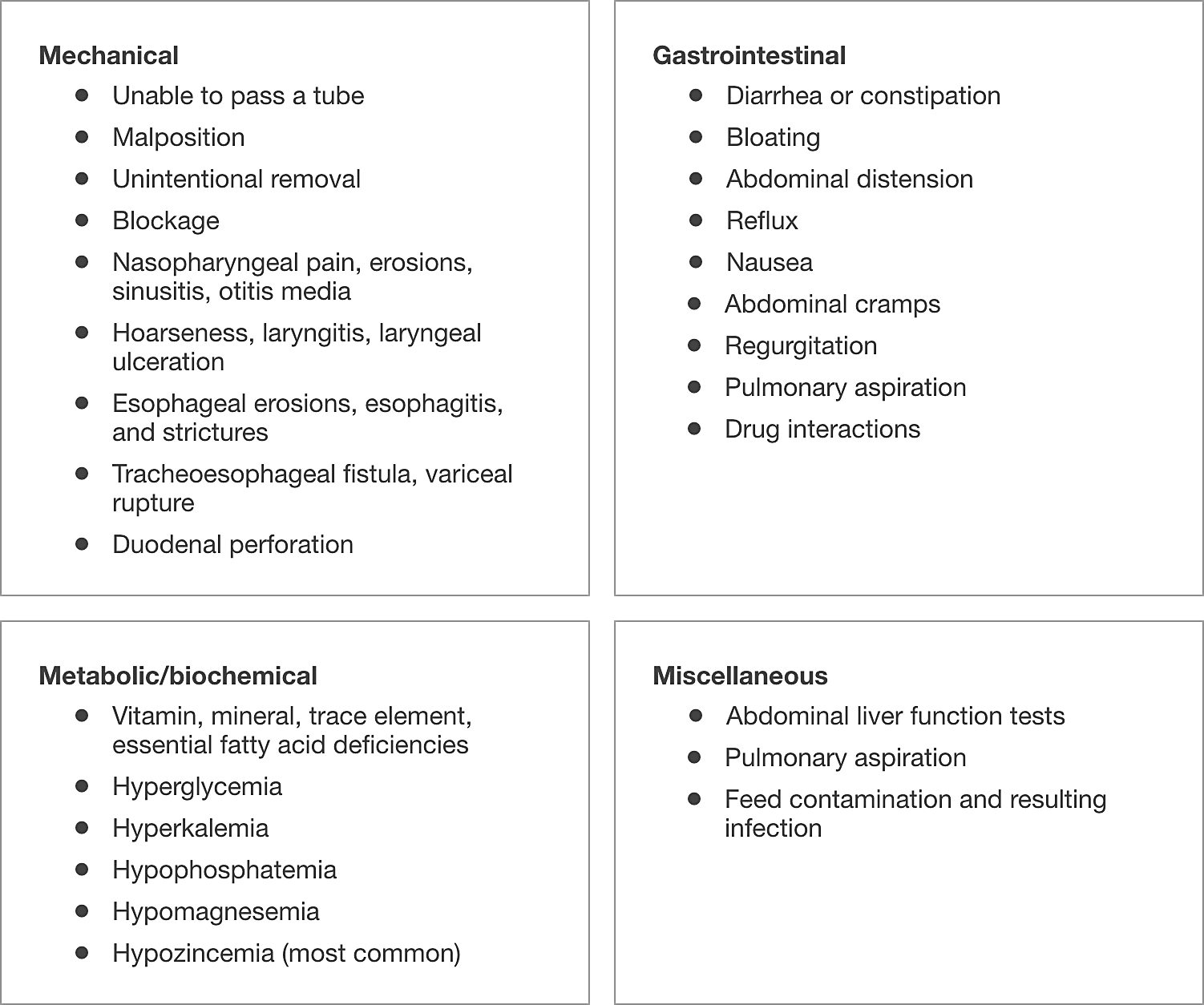

Table 6. Common Complications for Enteral Nutrition

The Common Complications for Parenteral Nutrition

Admixtures are concentrated (TPN formulas are more concentrated than PPN formulas) and runs the risk of thrombosis. Improper care of the port of insertion may lead to infection or sepsis.11

Moreover, regarding the body’s reaction to imbalances in the nutritional fluid, glucose abnormalities are common, so are hepatic complications, abnormalities in serum electrolytes and minerals, and gallbladder complications.7,12

The Timing of Nutrition Therapy

According to the latest ASPEN and SCCM guidelines, it is recommended that nutrition support therapy in the form of early enteral nutrition (EN) be initiated within 24−48 hours following the onset of critical illness and admission to the ICU and increase to goals over the first week of ICU stay.

As trophic feeding (low and slow) is advised, the recommended starting level of EN is hypocaloric, to be increased until the target within 3-7 days. If EN is contraindicated for the patient, such as in the case of uncontrolled shock, PN should be initiated within 3-7 days. Moreover, in a turnaround from the 2009 ESPEN guidelines, the current recommendation is to administer PN without glutamine.

If a patient is able to consume food orally and if the nutrition covers the 70% of daily nutrition demand starting from Day 3 until Day 7, an oral diet is preferred over EN and PN. Otherwise, early EN (within 48 hours) should be performed (rather than delayed EN and early PN). As mentioned earlier, PN should be considered only when oral and EN are contraindicated. Early and progressive PN is preferred over no nutrition at all. Moreover, to avoid overfeeding, early full EN and PN are contraindicated for critically ill patients until Day 3 until Day 7.

The Types of Formula that Make Up EN and PN

There are many types of formula that may be used for both EN and PN. It all comes down to the needs of the patient and, of course, safety. Usually, blenderized food is not recommended for EN because it carries a risk of a physical blockage of the tube despite being finely processed. Furthermore, there is a high risk of contamination and the accuracy of the exact nutrients needed may not be delivered. There are commercially available feeds for EN in the market that are specifically formulated according to the needs of the patient.

EN should be initiated low and slow. Trophic feeding aims to start with 30% of the daily requirement and gradually increase until 80% so that the GI system does not get too worked up immediately to cause hemodynamic instability.

One complication to observe during oral, EN, and PN is Refeeding Syndrome (RS). This happens when the patient suffers an abrupt decrease in potassium, magnesium, and/or phosphorus in the blood. This is caused by the pancreatic stimulation and insulin secretion following the introduction of a consistent nutrient source. Other clinical signs of refeeding syndrome include edema or swelling secondary to sodium and fluid retention, which can then cause stress to the heart and lungs.12

There are three types of EN feeds currently being used:

- Polymeric Feeds – indicated for those with normal or near-normal GI function. These come in various configurations of energy, protein, mineral, fat, vitamin, fiber, and water levels that will suit the patients’ needs.

- Elemental and Semi-Elemental Feeds – contain either pure amino acids or pre-digested protein. These are usually more expensive and indicated for patients with GI impairments.

- Disease-specific Feeds – can be used in severely ill patients with specific comorbidities. However, they are not generally indicated for long-term EN therapy.

In the critical care setting, protein appears to be the most important macronutrient for healing wounds, supporting immune function, and maintaining lean body mass. Peptides are more efficiently absorbed than intact proteins and can help manage gastrointestinal intolerance as 30-75% of nitrogen is absorbed in peptide form. Peptide carriers are less susceptible to depletion in certain disease states. Moreover, peptide-based formula increases blood flow to the gut and aids in maintaining gut integrity, consequently preventing bacterial translocation.13-16

Types of PN formulas:17,18

- All-in-One (AIO) and Multi-Chamber Bag (MCB) – contain standardized formulations for the patient

- Individual formulations – usually for long-term parenteral feeding

The Signs of Recovery

One of the most important markers for recovery among ICU patients is the level of protein. Once protein levels (i.e., albumin) stabilize, the outlook of the ICU patient improves. Considering that the ICU takes care of many patients with varying diseases, one important marker to look out for is blood sugar because highly stressed patients are prone to hyperglycemia, whether diabetes is a comorbidity or not.

In the gradual decrease of using EN or PN, it comes down to the patient’s tolerance for oral feeding and the stability of their condition. Of course, this would depend on the condition of the patient, and tolerance does vary across conditions. For example, a stroke patient may have a slower time to recover from dysphagia compared with a burn patient. The NST, headed by the clinical nutrition doctor, needs to assess, and decide the next steps to proceed.

Once the NST determines that the patient is well enough and can tolerate oral feeding, they will be put on a progressive diet. A progressive diet is a method that aims to slowly feed the patient first with liquids, then put them on a soft diet, and finally on a diet as tolerated. Care should always be taken to prevent aspiration.

The Post-Critical Care

After the patient’s ICU confinement, the patient is likely transferred into a hospital room or ward, where they continue their recovery, as well as adjustment to feeding. Usually, the RNDs and nurses instruct the primary caregivers of the patient about feeding. The patient may or may not remain dependent on EN or PN even following hospital discharge, and this will be decided based on their condition by the NST.

It is important to note that nutrition remains one of the most important factors during this time, and utmost care must be practiced by primary caregivers. Beyond the walls of the hospital, nutrition should remain guided until the patient fully regains his lost health.

Conclusion

Critical care demands concerted effort from all involved: the NST, the primary caregivers, and of course the patient. Careful planning and administration of nutrition is key to crafting the best outcome and shorter ICU stay. Part of this planning is the ongoing discussion among medical societies regarding the guidelines for critical care nutritional therapy, but one thing is for sure: at the moment, nutrition should always be individualized for the patient’s needs and corresponding conditions. Nutrition therapy and critical care should also consider the current status of healthcare in the Philippines. With the high cost of critical care, there needs to be more focus on planning for the patients and more actionable policies safeguarding health.

Dr. Jimmy Bautista

Dr. Jimmy Bautista

No comments here yet.