Battle of Nutritional Assessments: MNA vs SGA

Measuring nutritional status is becoming more accessible in this digital world. Bring in the smartwatches, electronic weighing scales, and mobile apps. One can easily measure and track their food intake and how active they are in an instant.

It is a different story, however, for the elderly and those in critical care. Assessing nutritional risk is a far more specific method. It is a process that if done early and efficiently, can largely improve the patient conditions and outcomes most especially for the frail, sick, and hospitalised patients.

Nutritional Assessment and Tools

Nutritional assessment is a method for identifying nutritional status in order to address it. Right now, there are two well-known and validated nutritional assessment tools being widely used in hospital and geriatric settings: the Mini Nutritional Assessment (MNA) and the Subjective Global Assessment (SGA).

Method 1: The Mini Nutritional Assessment (MNA)

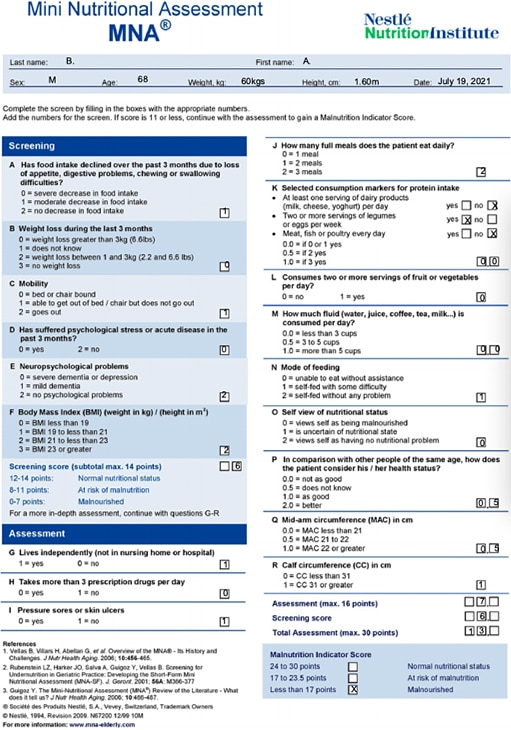

The MNA is a validated tool that was initially developed for use in geriatric patients aged 65 and above who are malnourished or at risk of malnutrition. The “MNA-LF” (‘MNA long form’), which is available in English and has been translated in many languages including Tagalog, has 18 items (Items A to R) and evaluates 4 areas.

This scoring has shown a 96% sensitivity, 98% specificity, and 97% predictive value1.

The shorter and more current version of MNA, the MNA-SF (“MNA short form”), contains 6 items that are more strongly correlated with nutritional assessment compared with the older version’s 18 items. The MNA-SF is used as a screening tool and cuts the time to 3 minutes compared with the usual 10 minutes for the overall questionnaire. Initially, the MNA-SF was used together with the MNA-LF. The MNA-SF has since been liberated as a standalone tool2,3 .

A score of 11 and below indicates the need for a full nutritional assessment1 .

The MNA-SF may also be used by patients (or their caregivers) as a self-assessment tool4.

Method 2: Subjective Global Assessment (SGA)

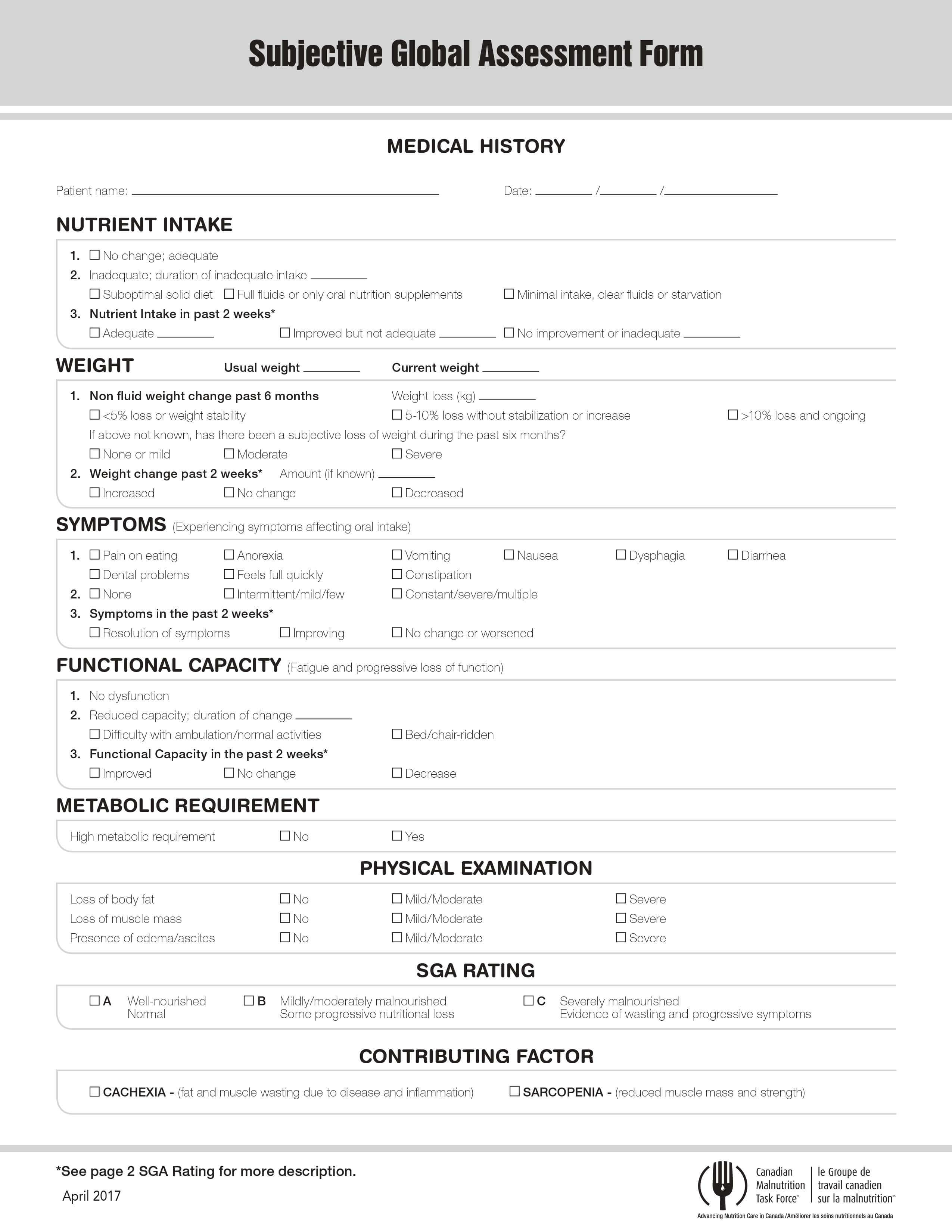

The SGA was developed by Dr. Allan Detsky in 1987. The SGA, which is administered upon admission and then regularly until discharge, considers two major areas, namely, medical history and physical examination, and classifies patients as well-nourished, moderately (or suspected to be) malnourished, or severely malnourished. Compared with MNA, which is used for the geriatric patient group, SGA can be used more widely for hospitalised patients, such surgical, oncological, renal, and geriatric groups.

The SGA is non-quantitative, thus it cannot be used to monitor changes in nutrition status.

Since its development, the SGA has been modified by many researchers and clinicians for different patient populations. The Philippine Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition (PhilSPEN) is among those that modified the SGA, in order to include objective measurements and scoring. The PhilSPEN Modified SGA includes BMI, serum albumin, and total lymphocyte count. The BMI in the PhilSPEN Modified SGA utilizes the WHO criteria according to a study on the index for the Philippine population. To fully describe the condition of the patient, the PhilSPEN Modified SGA also accounts for inflammatory markers, namely, serum albumin and total lymphocyte count (TLC). The PhilSPEN Modified SGA has been validated as highly specific and sensitive for malnutrition5. In fact, the tool is currently being utilized in several hospitals in the Philippines.

Head-to-Head MNA versus SGA

Both tools are easy to use, and in the case of their original versions, no laboratory tests are required. Thus, they are fast and inexpensive to implement. Moreover, their common domains include weight loss and recent poor intake. In cases of elderly patients, the MNA is more appropriate, due its criteria for functionality, depression, and dementia, which are more common in this patient group. On the other hand, the SGA may be applied to most cases and even the elderly. Unlike the MNA, the SGA takes into account the disease severity, which signifies increased nutritional demand in the patient.

Given these points, when choosing a tool, it comes down to which data points are needed to be assessed vis-à-vis the disposition of the patient. However, it is not unheard of to use both or either tools in assessing a patient.

In a study by Barone et al. (2003) on elderly patients, the MNA performed better in identifying severely malnourished patients than SGA. In a study by Bauer et al. (2005), they found it difficult to compare SGA with MNA and NRS due to the limitations of MNA for use within geriatric populations. Therefore, head-to-head comparisons of SGA and MNA seem to be lacking and may need further exploration.

Limitations of MNA and SGA

The MNA and SGA have limitations that have been shown in ICU settings. If the patient is not awake or stable, they may not be assessed for neuropsychiatric status and dietary changes. The MNA cannot be used for patients who cannot reliably provide self-assessment, such as patients who are confused, with advanced dementia, post-stroke aphasia, and severe acute diseases7. As for the SGA, since most patients in the ICU are classified as SGA C, they may not be categorized further, nor monitored for improvements in nutritional status by their care providers. Due to this, it may be difficult to identify which patients are at high risk for malnutrition. Furthermore, SGA and MNA cannot flag patients who are obese as being at risk for nutrition-related complications.

For patients in critical care, the Nutrition Risk in Critically Ill or NUTRIC score and the Nutritional Risk Screening 2002 or NRS 2002 are more appropriate for assessing nutritional risk, according to the American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition (ASPEN) and Society for Critical Care Medicine (SCCM) Guidelines in 2016. It needs to be mentioned, however, that the European Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition (ESPEN) Guidelines in 2019 disagrees with ASPEN and SCCM recommendation regarding the usage of NUTRIC and NRS 2002 due to acute critical illness-associated malnutrition still being undefined. In place of NUTRIC and NRS 2002, ESPEN recommends a general clinical assessment until a specific validated tool is developed.

Table 1. Nutritional Assessment Tool Applications and Selection Considerations (Queensland Health Dietitians, 2014; Nestle Nutrition Institute, n.d.)

| Tool | Applications | Parameters | Other Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Full MNA/ MNA-LF |

| Considers 18 Items across 4 general areas: Anthropometric measurement:

Global assessment (6

Short dietary questionnaire (8

Subjective assessment:

Scoring:

| Takes 10-15 mins to Wider usage in research |

| MNA-SF | Utilized as a validated screening tool | Considers 6 items:

Scoring: | Takes shorter than Full MNA while retaining accuracy and validity Both MNA formats may be challenging to use on patients in ICU For ICU patients, the NUTRIC Score is recommended. Both Full MNA and MNA- LF are well-validated in international studies and correlate with morbidity and mortality |

| SGA | Patient Groups: Geriatric, Surgical, Oncological, Renal Settings: Acute, Community, Rehab, Residential Aged Care Limited in Critical Care Settings. | Considers Medical History

Physical Examination

Classifies Patients as:

| Easy and fast to administer Has a wider patient group application. Unlike the MNA, the SGA takes into account disease severity SGA may not be accurate for ICU patients since all ICU patients are categorized as SGA C. Thus, patients may not be differentiated in terms of their risk for malnutrition For ICU patients, the NUTRIC Score is recommended by ASPEN SCCM but a general clinical assessment is recommended by ESPEN (as explained above). |

| PhilSPEN Modified SGA | Utilized in the local in- hospital setting | Same with SGA, but

Scoring system: | Compared with the original SGA, the PhilSPEN Modified SGA takes into account other factors, namely, BMI, TLC, and serum albumin. While these additional metrics may make the test more exhaustive, results may take time. |

Table 2. Guideline in Selecting MNA or SGA for Patient Assessment

| Patient Characteristics | MNA | SGA |

|---|---|---|

| 18-64 years old | No | Yes |

| >65 years old | Either MNA or SGA may be used | |

| Non reliable self assessment (demential/loss of consciousness) | No | Yes |

| Hospitalized | Either MNA or SGA may be used | |

| Community | Either MNA or SGA may be used | |

| Monitoring for Nutritional Improvement | Yes | No |

| No available anthropometric measurements | No | Yes |

Below are sample cases and their respective appropriate assessment tools, as well as the rationale behind choosing each tool. The third case is expanded and is used as the example for mock MNA and SGA results.

Table 3. Sample Patient Cases on Selecting MNA or SGA as the more appropriate Nutrition Assessment Tool

| Sample Cases | Appropriate Assessment Tool | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| At 83 year old female with stroke being cared for at home | MNA-SF | According to the ESPEN Guidelines for Clinical Nutrition and Hydration for the Elderly, the MNA is more appropriate for assessing geriatric cases or those 65 years old and above. |

| A 55 year old male with cancer being planned for admission to surgery | SGA | The SGA is used for the general population "For surgical patients "severe" nutritional risk

|

A 65 year old male patient on regular

Dietary History:

Physical Exam:

| Either MNA-SF/ Full MNA or SGA | Both tools may be utilized in this case. SGA

According to MNA score:

In this case, the SGA and MNA-SF are |

The following are the mock MNA and SGA forms for Case #3:

Mini Nutritional Assessment Form

Subjective Global Assessment Form

MNA and SGA have been widely adapted and validated and have been put into clinical use worldwide. However, the language around malnutrition, the condition that so many nutritional assessment tools are supposed to assess, remains to be ratified. The prevalence, interventions, and outcomes of malnutrition vary around the world, and addressing these major concerns can further improve measures of prevention. Thankfully, the Global Leadership Initiative in Malnutrition or GLIM has arrived at an approach for diagnosing malnutrition based on core phenotypic and etiologic criteria and said approach is waiting to be validated. Hopefully, once the GLIM consensus gets validated, the world can move ahead in the fight against malnutrition in terms of global standards.

In conclusion, we have discussed two well-validated nutrition assessment tools. The MNA is designed as both a screening and assessment tool for the elderly, whereas the SGA is validated for general adult outpatient and in-hospital cases. Due to their extensive utility in different clinical scenarios, familiarization with both the MNA’s and SGA’s features, scoring, and limitations is practical.

Dr. Joyce Bernardino

Dr. Joyce Bernardino

No comments here yet.