The Gut Microbiota and the Benefits of Good Gut Health

The gut microbiota is the collection of microorganisms residing within the digestive tract. There are many different strains of bacteria, the main phyla being Bacteroides and Firmicutes, and this diversity is crucial not just in digestive wellness but also in overall well-being.

Various products have claimed helpful to gut health, and these are probiotic-enriched sources, which can be food or a dietary supplement, and prebiotics. Probiotics and prebiotics, alone or in combination, have been studied for many years showing benefits in gastrointestinal conditions.1 Lately, the favorable effects of probiotics have extended past digestion and onto other areas, such as mental health and cancer.

What are Probiotics and Prebiotics?

Probiotics are live microorganisms in food. When these live microorganisms reach the intestines, they exert healthful effects, hence the moniker ‘good bacteria’.

On the other hand, prebiotics are the ‘food’ for the probiotics. Prebiotics are foods that are indigestible by the human digestive tract, so they can travel down the intestines. Once in the intestines, they are broken down via fermentation by the gut microbiota, thereby releasing short-chain fatty acids and other byproducts. These short-chain fatty acids and other fermentation byproducts are helpful to the gut, and cause changes that stimulate growth of the good bacteria. Ultimately, the interaction between a prebiotic and a probiotic is beneficial to the host.

Prebiotics are not just fiber, and not all fiber are considered prebiotic. Fiber needs to have all these characteristics to be considered a prebiotic2:

- resistant to the acidity of the stomach,

- not hydrolyzed by mammalian enzymes,

- not absorbed in the gastrointestinal tract,

- fermentable by the intestinal microbiota, and

- selectively stimulate the growth and activity of the gut environment and subsequently result in improved health.

Where are Probiotics and Prebiotics Found?

Common probiotic foods include yogurt, kombucha, kimchi, pickles, miso, sauerkraut, some cheeses, and other fermented foods. By far, yogurt is the most commonly marketed and consumed probiotic food due to its taste and texture. Moreover, yogurt is versatile as an ingredient to other recipes, and as a canvas, for other ingredients can be added to it.3 Aside from food, probiotics can also come from dietary supplements which are more specific in dosage and strain of bacteria, needing guidance from a healthcare professional. Furthermore, specific digestive problems respond well only to certain strains.

The question of whether the ‘live microorganisms’ in probiotic-packed yogurt can survive the acidity of the stomach should be addressed. Can they survive well and long enough to reach the intestines? Yes, with some caveats: it is recommended to consume probiotics at a certain temperature and with food to dilute the acid present in the stomach.

Inulin, an example of prebiotic, can be found in local foods,4 such as garlic, onion, shallot, dragon fruit, and jackfruit, whereas trace levels of prebiotics are present in wheat, bananas, oats, and soybean.5

Synbiotics: Probiotics and Prebiotics in One Treatment

A synbiotic is a combination of a probiotic and a prebiotic, and this synergy is believed to have an enhanced effect compared with prescribing a probiotic or a prebiotic alone. One example of synbiotic therapy involves Bifidobacterium longum and psyllium.6 Further studies are needed to explore the scope of synbiotics’ benefits in healthcare.

How do Probiotics work?

The known mechanisms through which probiotics benefit the body are diverse. While there have been documented gains from probiotics, studies are still exploring to ascertain their fullest extent. Remember, a probiotic can do a lot of good for the gut. 7

Probiotics maintain and enhance the epithelial barrier of the intestines. This way, bacteria and foodborne pathogens do not get through to the deeper layers of the gut and cause inflammation and infection. Probiotics enhance adhesion to the intestinal mucosa, and adhesion can further modulate immunity and defend against pathogens. Moreover, intake of probiotics helps prevent the binding of pathogens to the gut wall.

Probiotics induce the release of defensins, which fight bacteria, fungi, and viruses, from epithelial cells in the gut. One interesting mechanism that is secondary to consumption of probiotics is ‘competitive exclusion’ of pathogenic microorganisms, or the creation of an environment that is uninhabitable for pathogens.

Probiotics can confer immunomodulatory protection to the host.

| defensins: peptides of neutrophils and epithelial cells, displaying roles in direct antimicrobial activity, immune signaling activity, or both |

How Should Probiotics Be Prescribed?

Generally, probiotics are not prescribed as primary treatment. As there is limited evidence regarding dosage, they are not regulated. However, some studies have identified certain gastrointestinal conditions that may be alleviated by certain probiotic strains (Table 1). When starting intake of specific strains for certain conditions, it is important to seek advice from a nutritionist-dietitian or doctor, as well as to start low and slow.

Table 1. Probiotic as treatment for diseases (Wilkins & Sequoia, 2017)

| CONDITION | PROBIOTIC SPECIES | RECOMMENDED COLONY-FORMING UNITS (CFU) | STUDY/SOURCE |

|---|---|---|---|

| Normal | Enterococcus faecium Streptococcus thermophilus | 10 billion cfu per day | Wilkins and Sequioa (2017) |

| Helicobacter pylori | Streptococcus thermophilus | 108 cfu/mL, 150 mL, q.d., for 4 weeks | Zheng, Lyu and Mei (2013) |

| Irritable bowel | Streptococcus thermophilus | 2.5 x 1010 cfu/day | Zhang et.al (2016) |

| Colic | Lactobacillus reuteri ATCC 55730/DSM 17938 | 108 cfu in 5 drops for 28 days | Anabrees, et.al (2013) |

| Necrotizing | Bifidobacterium adolescentis, animalis subsp lactis, bifidum, breve, longum, longum subsp infantis | Approximately 3 billion cfu/ day of each organism for the first seven days of life | AlFaleh and Anabrees (2014) Olesen, et.al (2016) |

It bears repeating that therapeutic intake of probiotics and prebiotics entails close communication with your health provider. It is important to keep in mind that probiotics and prebiotics cannot substitute for medicine. At best, probiotics and prebiotics will be supportive to the main treatment regimen.

Other Benefits of Probiotics

The Growing Problem of Obesity and Overweight

Overweight and obesity continue to make dents in society by increasing the risk of lifestyle-related and noncommunicable diseases (NCDs), such as hypertension, type 2 diabetes, stroke, and heart disease. Beyond the health implications, there are economic impacts to deal with as NCDs require treatment, pose disease burden, and could decrease productivity. 9 This less sensationalized global epidemic has gone on for decades, and while research has discovered more and more ways to live healthier and medical professionals have continually counseled patients and educated the public on the importance of healthy living, these efforts have not translated to favorable results.

Probiotics for Obesity

Obese and overweight patients have presented with low assortment of microbiota, or dysbiosis. Dysbiosis has been observed in patients with inflammatory bowel disease, types 1 & 2 diabetes, celiac disease, and arterial stiffness. While a direct connection between bacterial diversity and obesity cannot be drawn at the moment, there is a growing body of evidence relating the two. Therefore, addressing microbiome diversity in the fight against obesity remains sensible.10

Other effects of probiotics in obesity is lowering the absorption of dietary fat and releasing appetite-regulating hormones and fat-regulating proteins. Additionally, probiotics can prevent systemic inflammation by improving the health of the epithelial layer of the gut, as mentioned previously; this mechanism can in turn help prevent obesity and other digestive conditions. However, more evidence is needed to substantiate such claims.

Probiotics for Immunity

Probiotics have been linked to immunity over the past years. They regulate the function of immune cells and intestinal epithelial cells, thereby leading to possible interventions for allergies, viral infections, and even in boosting vaccine response. A recent study suggested that immune cell responses are specific to probiotic genes, and the functions of these probiotic genes also depend on the microenvironment of the host.11

Moreover, a study showed that during an infection in the respiratory tract, body receptors signal immune responses through the gut-lung axis, which is a bidirectional pathway via the blood and lymphatic system. 12 Therefore, the gut microbiota can act as an immune system regulator in the pulmonary area. Probiotics enhance the airway (T-regulatory response) and this triggers lung immunity. Additionally, the study showed microbial elimination through natural killer cells, neutrophils, and alveolar macrophage. There have been random trials on COVID-19 patients using probiotics, but evidence is lacking to impact on mortality rate and other endpoints.

“Gerobiotics”: Probiotics for Longevity

An aging world population means having to treat more geriatric cases. Recently, studies have shown that a healthy gut may help in managing age-related conditions, thereby promoting longevity, and improving quality of life. “Gerobiotics”, a portmanteau of ‘gerontology’, the study of aging, and ‘probiotics’, is a new term being proposed.

In general, probiotics are safe to consume for the elderly population, and it has been proven to still improve immunity and gut health. Beyond these benefits, studies have shown that certain strains can improve certain aging-related markers. L. plantarum C29 and L. paracasei PS23 experiments in mice have shown improved memory, reduced inflammation markers, decreased senescence markers, and improved cognition. L. paracasei PS23 also reduced age‐related sarcopenia and enhanced antioxidative capacity to modulate inflammation.13

Probiotics for Anti-Inflammation

Probiotics have long been used for a range of inflammatory conditions, such as inflammatory bowel syndrome or IBS, ulcerative colitis, and Crohn’s disease. These conditions and their related flare-ups have been shown to present with imbalances in the gut microbiota.

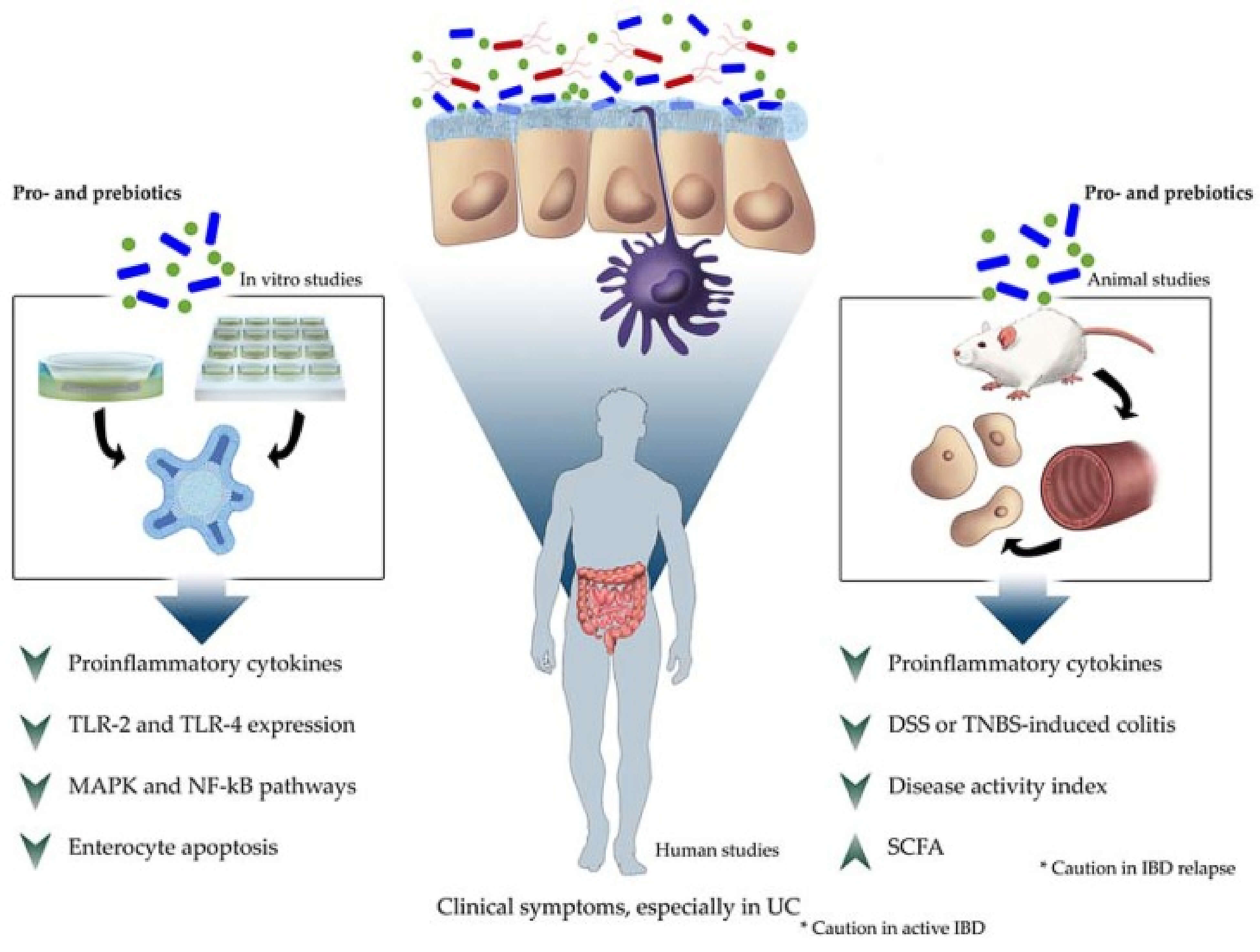

In in vivo studies in animals, probiotic supplementation has shown to have protective effects on induced colitis. This effect happened through downregulation of inflammatory cytokines or by inducing regulatory mechanisms depending on the strain of the probiotic used (Figure 1). In another study,15 intrarectal administration of mouse cathelin-related antimicrobial peptides showed alleviation of colitis secondary to preservation of the mucus layer and reduced production of pro-inflammatory cytokines.

In humans, similar anti-inflammatory effects were observed. However, it should be noted that since probiotics have a wide array of strains, there needs to be increased focus on the reaction of the patient, their inflammatory markers, and their conditions to each administered strain. Moreover, further study is needed into the area of probiotics as a management option for diseases that present mainly with inflammation of the bowels.

Figure 1. Summary of probiotic anti-inflammatory effects in intestinal chronic diseases in different scientific approaches (Plaza-Díaz et al., 2017)

The Gut-Brain Axis

The Gut-Brain Axis (GBA) is a bidirectional path of communication between the central nervous system and the digestive tract. The gut microbiota can influence these interactions via neural, endocrine, immune, and humoral connections.16 However, the role of the gut microbiota in the GBA and the extent of its influence needs further studying. So far, the gut microbiota has been seen to influence depression and anxiety-like behaviors, including specific patterns of microbiota presentation in cases of autism.

A new category of medicine, called ‘psychobiotics’, is currently being explored for its effects. Researchers have yet to find conclusive evidence linking the health and diversity of microbiota or bacteria strain to specific mental health conditions.

Treatment for Schizophrenia and other Mental Health Conditions

The link of dysbiosis and schizophrenia and other mental health concerns, such as anxiety and depression, has been a topic of study for years. Although current findings call for further elucidation, there have been some encouraging results.17 As above, there is not yet a clear connection between certain mental health issues and intake of probiotics, and more studies, specifically human studies, are needed to further elucidate these hints.

Conclusion

What we know about probiotics and prebiotics has greatly expanded through decades of research. Evidence has suggested numerous novel benefits, but not that many claims have been incontrovertibly proven. Thus, while patients can enjoy their choice of probiotics and prebiotics that are widely available in the market, healthcare providers should practice due diligence in advising patients on possible drawbacks of their misuse. It is also good to remind patients that probiotics are not medicine, and thus should not be considered as such. In most if not all medical conditions, shifting to a healthy diet and a more active lifestyle, with a generous serving of good bacteria, is the key.

Dr. Tricia Guison-Bautista

Dr. Tricia Guison-Bautista

No comments here yet.